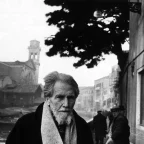

PRESENTATION

Kostas Kremmydas was born in Kolonos (Athens) in August 1955. He studied Political Science and Public Administration at Panteion University, Pedagogy at the School of Pedagogical and Technological Education (former SELETE), Law at the University of Athens and Social History at the Sorbonne University, where he completed his master’s thesis entitled Trading Union Movement and Banks in Greece (1917-1949): the case of the National Bank of Greece.

He holds a doctoral degree from the University of Patras in Τhe pedagogical role of the Magazine Art Review (1954-1967). From 2000-2018 he participated in the Organizing Committee of the Poetry Symposium. Since 2016 he has been teaching creative writing at the Postgraduate Department of the Hellenic Open University. He has participated in several literary publications. Since 1993 he has been managing Mandragoras Magazine and the homonymous editions, which exceed 300 book titles.

He has published one volume with political chronographs entitled “corner of Xouthou & Menandrou, End of Ephoxi (2014) and the autobiographical novel Redwhite Madness, Red Tulips in Kolonos (2017).

He has published six poetry collections: Elevator, An Unfinished Intercourse (1993), Ode to Trolleys (1995), In favor of Heroes (1998), Mobile texting (2002), Chandigarh (2013). With Alexandros Arabatzis he has published the collection Light errant poems, within the limits of Political correctness (2014). His poems have been translated into Bulgarian by Christos Hartomatsidis.

*

O Kώστας Kρεμμύδας γεννήθηκε στον Κολωνό τον Αύγουστο του 1955. Σπούδασε στα τμήματα Πολιτικών Eπιστημών και Δημόσιας Διοίκησης στο Πάντειο Πανεπιστήμιο, παιδαγωγικά στη ΣEΛETE, νομικά στην Aθήνα και Kοινωνική Iστορία στη Σορβόνη, όπου παρουσίασε το μεταπτυχιακό του: Συνδικαλιστικό κίνημα και Τράπεζες στην Ελλάδα (1917-1949), Η περίπτωση της Εθνικής Τράπεζας. Διδάκτωρ του Πανεπιστημίου Πατρών όπου εκπόνηση διατριβή για τον Παιδαγωγικό ρόλο της «Eπιθεώρησης Tέχνης» (1954-1967). Το διάστημα 2000-2018 συμμετείχε στην Οργανωτική Επιτροπή του Συμποσίου Ποίησης. Από το 2016 διδάσκει στο Μεταπτυχιακό Τμήμα Δημιουργικής Γραφής του Ελληνικού Ανοικτού Πανεπιστήμιου. Συμμετείχε κατά καιρούς σε πολλά λογοτεχνικά έντυπα. Από το 1993 διευθύνει το περιοδικό και τις ομώνυμες εκδόσεις Mανδραγόρας. Έχει εκδώσει έξι ποιητικές συλλογές, έναν τόμο με πολιτικά χρονογραφήματα Ξούθου & Μενάνδρου γωνία, Τέλος Εποχής και την αυτοβιογραφική νουβέλα Ερυθρόλευκη τρέλα, Κόκκινες τουλίπες στον Κολωνό. Ποιήματά του έχουν μεταφραστεί στα βουλγαρικά από τον Χρήστο Χαρτοματσίδη.

Έχει δημοσιεύσει τις ποιητικές συλλογές Tο ασανσέρ, Mια ημιτελής συνουσία, Ωδή στα τρόλεϋ, Yπέρ ηρώων, Μηνύματα σε κινητό, Σαντιγκάρ και με τον Αλέξανδρο Αραμπατζή τη συλλογή Ποιήματα μικρόσωμα άσωτα και φαντασμένα στα όρια του πολίτικαλ κορέκτ.

* * *

My mother’s bread

to Christos Hartomatsidis

My mother was always bending

leaning over the plastic basin

with one steady hand and

her right hand disabled, swollen

and red -how red, my Lord- a fire

in the all-white flour.

The yeast melts, the small knots are translucent

the anise, the caraway, the salt fall like the rain

And I stand aside, slowly pouring the flour

as if it is snowing in the kitchen

And as I was boiling water on the stove

because it needs to be lukewarm to be knead, they say,

I see tears falling in the basin

just enough for the flour to absorb them

they are falling

mother is kneading and kneading and kneading

I throw snowy flour in the snowy room

the knots are loosened and so is her soul

Years later, I found her again in the same place

kneading and kneading and kneading

crying and crying and crying

A skeleton faintly glowing in the empty room

Only her hand was still red

a bright-red fire that warmed her tears

drop after drop slowly falling

in the plastic basin

And kind of like that, her holy body

became the bread of the eternal life

*

Το ψωμί της μάνας μου

στον Χρήστο Χαρτοματσίδη

Λύγιζε κάθε τόσο η μάνα μου

σκυμμένη πάνω απ’ την πλαστική λεκάνη

με το ένα χέρι σταθερό και το

δεξί ανάπηρο τουμπανιασμένο

και πόσο κόκκινο-φωτιά θεέ μου

ανάμεσα στο ολόλευκο αλεύρι.

Λιώνει η μαγιά λύνονται διάφανοι μικροί λεπτοί οι κόμποι

Βροχή γλυκάνισο, το κύμινο, τ’ αλάτι

Εγώ από δίπλα αργά αργά ρίχνω αλεύρι

σαν να χιονίζει μέσα στην κουζίνα

Και πάνω που ετοίμαζα νερό στη σόμπα

γιατί χλιαρό, λένε, το θέλουνε στο ζύμωμα

βλέπω να πέφτουν αχνιστά τα δάκρυα στη λεκάνη

με αναλογία σταθερή ίσα για να τα πιει το αλεύρι

εκείνα τρέχουν

η μάνα να ζυμώνει να ζυμώνει να ζυμώνει

εγώ ρίχνω αλεύρι χιονισμένο στη χιονισμένη κάμαρη

οι κόμποι λύνονται μαζί με την ψυχή της

Μετά από χρόνια την ξαναβρήκα στην ίδια θέση

να ζυμώνει να ζυμώνει να ζυμώνει

να κλαίει να κλαίει να κλαίει

Ένας σκελετός που φέγγιζε στ’ άδειο δωμάτιο

Μόνο το χέρι της έμενε κόκκινο κατακόκκινη

φωτιά που ζέσταινε τα δάκρυά της

σταγόνα τη σταγόνα για να κυλά

σιγά σιγά στην πλαστική λεκάνη

Και κάπως έτσι έγινε άρτος ζωής αιώνιας

το σώμα της το άγιο

* * *

My father was famous

My father was famous

that’s why at his funeral

no one said a eulogy

he wasn’t even buried in state funeral

the flags did not fly at half-staff.

He was not Tydeus’ son

neither Oene’s grandson

having left Argos too soon

he was forgotten in some Unwritten pages.

My father was famous

he ignored the newspapers’ headlines

the oval television altars

the long detachements

the glamorous horsemen’ costumes.

My father was famous

each morning and night

in his place

wherever put, he stood there waiting.

My father was famous

with a fractured skull

he came down into my hands at nights

talking.

My father was famous

in the obituaries

on the piles of reclaimed soil

in the ruins of fossilized documents

in the news’ vulgar outcome.

My father was famous

to the gods and demons

in the absent rituals

in the remission of sins.

He prayed not, he used to leave in the evenings

lengthening, shrinking and tip toeing.

There is no point talking about one’s father

when he happens to be famous.

I tried to explain to some people

the supremacy of a distinction, though in vain.

My father was famous

and yet he never found a place in my agenda

I remembered his number by heart.

therefore

no deletions needed now.

After all, I have been keeping the same agenda for years. That’s why

all my deads

remain present.

*

Ο πατέρας μου ήταν διάσημος

Ο πατέρας μου ήταν διάσημος

γι’ αυτό στην κηδεία του

δεν εκφώνησε κανείς επικήδειο

δεν ετάφη καν δημοσία δαπάνη

δεν κυμάτισαν οι σημαίες μεσίστιες.

Δεν ήταν γιος του Τυδέα

μητ’ εγγονός του Οινέα

πολύ νωρίς εγκαταλείποντας το Άργος

ξεχάστηκε σε κάποιες Άγραφες σελίδες.

Ο πατέρας μου ήταν διάσημος

αγνόησε τα πρωτοσέλιδα εφημερίδων

τις οβάλ τράπεζες της τηλεόρασης

τα παρατεταμένα αγήματα

τις λαμπερές στολές των ιπποκόμων.

Ο πατέρας μου ήταν διάσημος

κάθε πρωί και κάθε βράδυ

στη θέση του

όπου να τον απέθεταν εκεί στεκόταν

και περίμενε.

Ο πατέρας μου ήταν διάσημος

μ’ ένα κρανίο ανοιχτό στην άκρη

κατέβαινε στα χέρια μου τις νύχτες

και μιλούσε.

Ο πατέρας μου ήταν διάσημος

στα αγγελτήρια θανάτου

στις σωρούς των αναπεπταμένων χωμάτων

στα ερείπια απολιθωμένων εντύπων

στων ειδήσεων τη χυδαία έκβαση.

Ο πατέρας μου ήταν διάσημος

στους θεούς και τους δαίμονες

στις απούσες τελετουργίες

στα σχετικά με τις αφέσεις αμαρτιών.

Δεν προσευχόταν, έφευγε τα βράδια

μακραίνοντας, μικραίνοντας κι αχνοπατώντας.

Δεν ωφελεί να πει κανείς για τον πατέρα του

όταν συμβαίνει ενίοτε να ‘ναι διάσημος.

Προσπάθησα σε κάποιους να εξηγήσω

για την υπεροχή μίας διάκρισης, επί ματαίω.

Ο πατέρας μου ήταν διάσημος

κι όμως ποτέ δεν βρήκε θέση στο καρνέ μου

θυμόμουν απέξω το τηλέφωνό του.

δε χρειάστηκε επομένως ν’ ακολουθήσουν τώρα διαγραφές.

Άλλωστε φροντίζω να διατηρώ από χρόνια

την ίδια πάντα ατζέντα. Είναι γι’ αυτό που

όλοι οι νεκροί μου

παραμένουνε παρόντες.